Countries, companies and other coalitions are setting climate goals to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to ‘net zero’ or limiting them to a 1.5° compatible level as set by the Paris Agreement. Individuals may wonder about their contributions to these climate goals. Can an average EU resident achieve a 1.5° lifestyle… without making lifestyle changes?

Our research aims to provide more information about the share of GHG emissions reductions that can be accomplished with extensive industrial decarbonisation – and the share of emissions reductions that must still come from individuals.

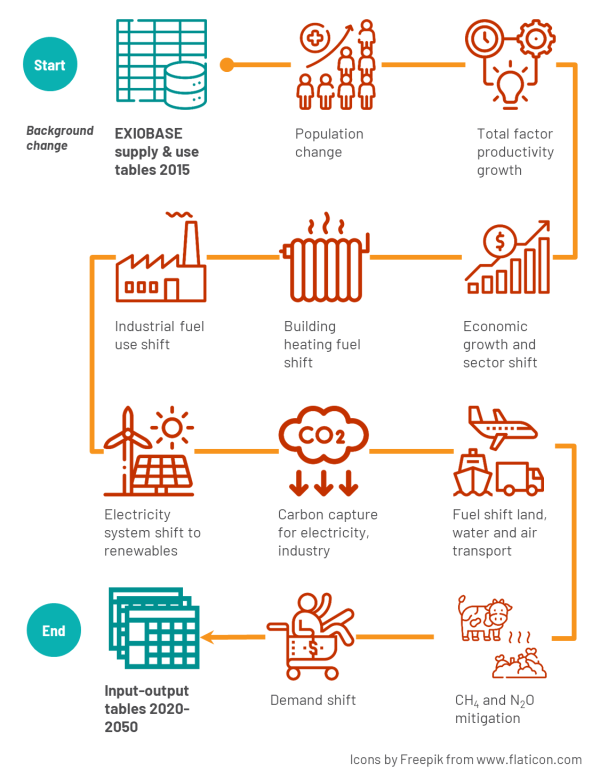

In this work, we quantified the limits for climate overshoots resulting from only ‘background’ changes to GHG emission levels within the global economy. Background changes refer to socio-economic and industrial developments that impact GHG emissions, such as greater economic productivity or a shift to a renewable energy system. We applied these changes to a model of the global economy that links spending on products and services to emissions associated with the provision of that economic good (known as an environmentally-extended input-output model). The projected changes were based on a pathway compatible with 1.5° of warming achieved through greater social and economic equality and technological innovation (SSP1-RCP1.9).

Of course, some aspects of decarbonisation require individual actions rather than only industry or government measures. Replacing a conventional car with more sustainable mobility options can be encouraged by government policy but still requires behaviour change. The same is true for household energy retrofits, dietary changes, and leisure travel. We purposefully excluded these changes from modelling to highlight how individual carbon footprints might evolve without individual behavioural shifts towards a 1.5° lifestyle.

Once the model was adjusted to reflect future populations and production inputs for economic activities, we calculated individual consumption-based footprints that reflect these future background system changes. National consumption-based household footprints (discussed in last month’s post) were divided by population projections for an equal per-capita target. We compared these footprints against carbon targets derived from a 1.5°C-compatible carbon budget with low reliance on negative emissions technology.

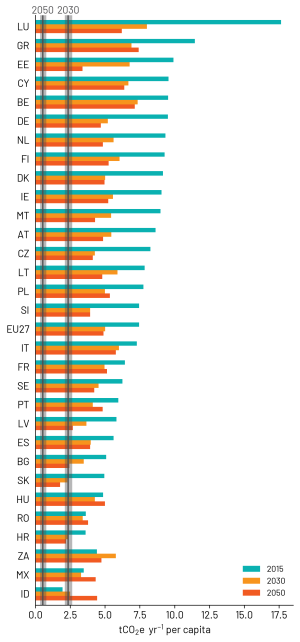

So what did we find? The results highlight the importance of behaviour change within the European Union (EU). With background changes alone, only one of the EU countries is projected to meet the 2030 climate target and no country is projected to meet the 2050 target (Figure 2).

For the median 2030 target (2.35 tCO2e yr-1 per capita), Slovakia meets the projected target, and Croatia narrowly misses the target with a 1% overshoot. Luxembourg and Belgium’s footprints are projected to be more than double the 2030 target. In 2050, EU27 overshoots ranged from 2.5 to 13 times the 2050 target (0.53 tCO2e yr-1 per capita).

Three G20 countries outside of Europe (Indonesia, Mexico, and South Africa) were also studied to contrast with the EU. Indonesia has the smallest projected footprint in 2030 at 2.5 tCO2e yr-1 per capita, a 6% overshoot of the 2030 target. As with the EU27, none of the three countries is projected to meet the 2050 target without behaviour change.

Some countries’ footprints are even projected to increase over time, as rising consumption activity coupled with less efficient technology outpaces background decarbonisation. Increased household income stimulated by rising economic growth and productivity is projected to lead to more consumption, such as frequent private car transport and larger houses with additional heating and cooling demand. To achieve climate targets, these changes must be offset by the adoption of more sustainable technologies or a sufficiency mindset.

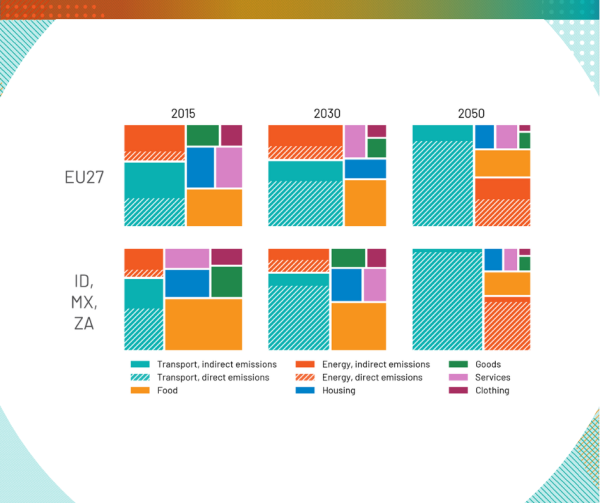

Across all scenario years, transportation, household energy, and food comprise the largest share of emissions in the EU and the three G20 countries. Transportation emissions overtake food by 2030 in the G20 countries, as shifting expenditure patterns rebalance from essential to more discretionary spending.

(In)equality also has a role in shaping carbon footprints. The overall carbon footprint of wealthy individuals tends to be larger than that of a less wealthy ones due to more consumption overall. This is despite the fact that the overall emissions intensity per monetary unit may be less in comparison for a wealthy household. An equal footprint target would thus demand much greater relative reductions from households with larger footprints derived from high income.

Overall, our research on how future carbon footprints compare to climate goals demonstrates the importance of individual behaviour change in climate change mitigation.

Stephanie Cap and Laura Scherer, Leiden University

Source of pictures: EU 1.5° Lifestyles consortium partners (c)